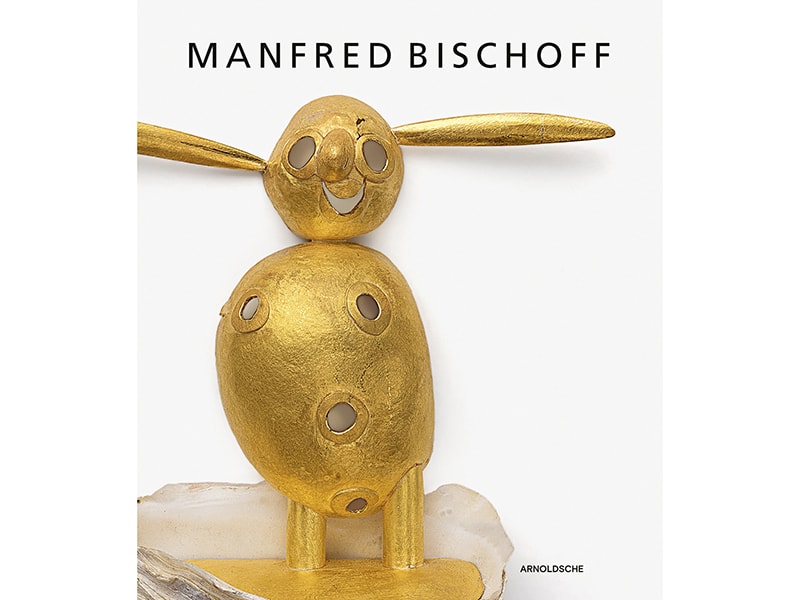

Manfred Bischoff: Ding Dong, Rike Bartels, ed., with contributions by Cornelie Holzach, Liesbeth den Besten, Matthew Drutt, Helen W. Drutt English, and Karl Bollmann, book design by Gabi Veit (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2021).

Even for those of us who love and are surrounded by books, every once in a while there will be one that comes to exist well beyond its papery goodness and the knowledge it shares: one that shows us the true agency of a book. These are books that insinuate themselves into our very fabric. Different books for everybody, but when we encounter one, we know it is there to stay in our personal imaginary, at once managing to open up a world for the first time, yet making us recognize this world as one we have somehow known and belonged to all along.

When these books find us, we are nearly overwhelmed, in this increasingly digital age, by the intangible power of their physical presence. The experiences of such encounters are rare, and all the more memorable. In the jewelry world specifically, I still vividly remember being shown Hermann Jünger’s Jewellery – Found Objects by none other than Bob Ebendorf, on that very first and life-changing encounter with him at West Dean College. I spent years tracking a second-hand copy down, finally celebrating the serendipity of obtaining one through another great teacher and mentor, Elizabeth Turrell. Or discovering, on the Ruthin Craft Centre’s stand at Collect, Paul Preston’s little unassuming autobiographical and eponymous spiral-bound treasure while tumbling down the Red Mole’s (Preston’s chosen pseudonym) tunnel into a golden miniature world that seemed so removed from the hustle and bustle of the art fair. Or flicking through published material on the quiet front windowsill at Maurer-Zilioli in Munich and discovering Bruno Martinazzi’s Memory Maps catalog (a rare copy of which Dr. Ellen herself, its editor, allowed me to buy!) and losing myself over and over in the immensity of his neatly scribbled pencil reflections.

Manfred Bischoff: Ding Dong is a tender, elegant, and moving tribute to an individual many of us have not had the opportunity to have in our lives, through the eyes of some of those who had the fortune to . What would normally read, in a scholarly publication, as an exclusive cast of jewelry writers (Cornelie Holzach, Liesbeth den Besten, Matthew Drutt, Helen Drutt English, Karl Bollmann), is here a list of close friends and admirers. There is musing in the writings, as there is reminiscence, searching, and questioning. Their contributions transcend the catalog essay to become the heartfelt testimonials and intimate, emotional insights of five humans not providing fast answers to increasingly hungry readers but still slowly seeking, even after so many years, to make sense of a man, his work, his universe. And of their personal, as well as that of the wider art world, loss.

Matthew Drutt and Liesbeth den Besten’s pieces, leaning more on the academic side, cannot but betray a sense of mystery about the man and the artist, his life and his creative process. Drutt calls this unclinchable complexity “Bischoffism”[i]; Den Besten describes it as “a door slightly opened” through which “you can grasp the atmosphere inside, be enchanted, feel the energy, but you can’t fully enter.”[ii]

All of the writings invariably also draw on first encounters with Bischoff, and the years of friendships and discussions that ensued. Karl Bollman’s “Thinking Of”—nearly each paragraph starting with the invocation “Manfred”, as if attempting to still talk directly or summon the presence of the man—is penned as much as an ode as a memoir. Helen Drutt’s collected recollections from Bischoff’s memorial strive to retrace, the way perhaps never destined to be clear, the unfathomable myriad of connections and shared meandering of mind, from common friendships to intellectual interests, that pulled and kept them together. “Deep in Manfred’s mind was a place where the world stopped and the imagination began and we entered his inner self.”[iii]

As an object, the book is an exquisite example of Arnoldsche’s ethos of creating publications that are bound not to an editorial house style but only to the specific demands of the content. As a celebratory monograph, the book has a wonderful feel as it so effectively combines the grandiosity of what is a very large coffee table format with the delicate airiness of its graphic design.

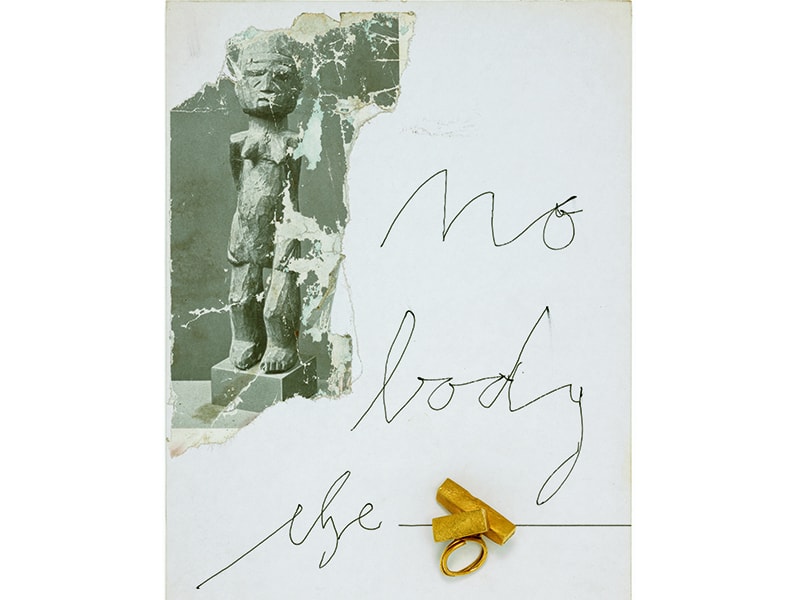

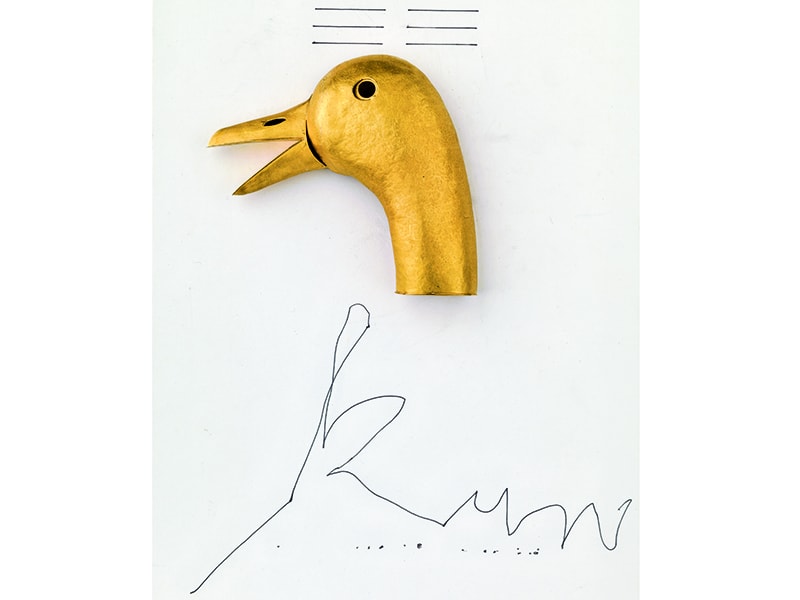

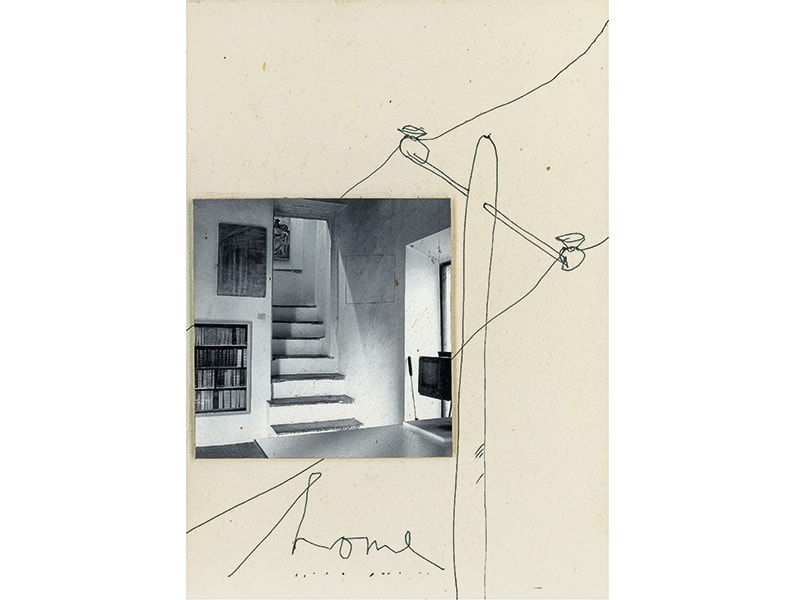

Spread after spread, the work is splendidly reproduced in actual size, which, from a research point of view, is always a most welcome practice, and particularly important for appreciating its visual symbolism and storytelling. But this is also crucial in order to try and unravel the uncanny complexity of that laboriously simple drawn and written line—a distinction sometimes so blurred as to be elusive, as in Kun[iv]—that forms so intrinsic and inextricable an element in Bischoff’s work. The focus of den Besten’s essay, this line remains clear and yet ungraspable in all of our imaginaries. And “Can we ever forget his script?” asks Helen Drutt: “his cursive writing announcing his presence on earth … a drawing … a linear road one had to follow to find Manfred’s “pot of gold.”[v]

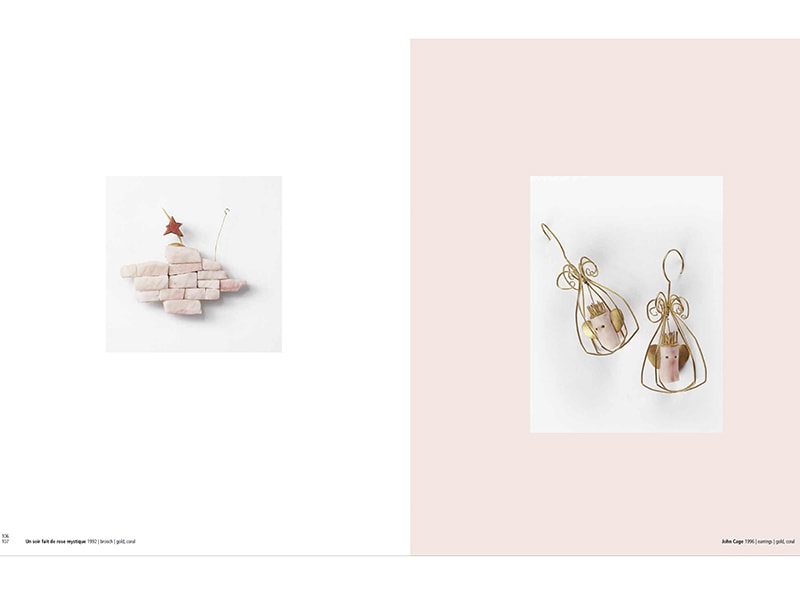

Beneath the fun dust jacket, featuring a towering Afrodite, one of Bischoff’s typically whimsical but inscrutable characters, lies a muted pink binding that is so intelligently layered with associations with the ethereal, the gentle, and the recherché. But this pink, which returns in two different tones throughout the book as an unexpected and deceptively inconspicuous page background, of course also matches the tones of the coral so often part of Bischoff’s opus—the bricks of Un soir fait de rose mystique and the faces of the John Cage earrings being a perfect example[vi]—subtly bridging the materiality of the book with that of the work.

Beneath the fun dust jacket, featuring a towering Afrodite, one of Bischoff’s typically whimsical but inscrutable characters, lies a muted pink binding that is so intelligently layered with associations with the ethereal, the gentle, and the recherché. But this pink, which returns in two different tones throughout the book as an unexpected and deceptively inconspicuous page background, of course also matches the tones of the coral so often part of Bischoff’s opus—the bricks of Un soir fait de rose mystique and the faces of the John Cage earrings being a perfect example[vi]—subtly bridging the materiality of the book with that of the work.

And then there are the photographs of the many of those Tuscan buildings and interiors—house indistinguishable from studio space—that were such an important environment to Bischoff. Most of these photographs were obtained through friends and colleagues, many after his passing: another wonderful touch reminding us of the emotional, as well as of the scholarly, role of the book. Cornelie Holzach shows a profound awareness of the relationship between place, man, and work, so much that half of her Foreword is taken up by the journey she undertook to Tuscany, a precursor to another, no less emotional nor less winding journey, into Bischoff and his world. The pink background here becomes an unassuming but warm brown (how had I not noticed the endpapers?), an old colour, matching the “cracks [of] the old monastery walls,” whispering of “fragile beauty,” faithful and undemanding like Bischoff’s “very old, very decrepit-looking dog.”[vii]

And then there are the photographs of the many of those Tuscan buildings and interiors—house indistinguishable from studio space—that were such an important environment to Bischoff. Most of these photographs were obtained through friends and colleagues, many after his passing: another wonderful touch reminding us of the emotional, as well as of the scholarly, role of the book. Cornelie Holzach shows a profound awareness of the relationship between place, man, and work, so much that half of her Foreword is taken up by the journey she undertook to Tuscany, a precursor to another, no less emotional nor less winding journey, into Bischoff and his world. The pink background here becomes an unassuming but warm brown (how had I not noticed the endpapers?), an old colour, matching the “cracks [of] the old monastery walls,” whispering of “fragile beauty,” faithful and undemanding like Bischoff’s “very old, very decrepit-looking dog.”[vii]

The man himself is mostly not in, but not absent from, these pictures. The empty steps, chairs, windows exert such evocative power, which I feel even more as an Italian who left similar places nearly 30 years ago. But if these walls and the objects they frame can only really have special meaning for those who have inhabited or shared them with him at one point or another, in the book they invite us to follow Holzach on our own Manfred Bischoff journey.

The man himself is mostly not in, but not absent from, these pictures. The empty steps, chairs, windows exert such evocative power, which I feel even more as an Italian who left similar places nearly 30 years ago. But if these walls and the objects they frame can only really have special meaning for those who have inhabited or shared them with him at one point or another, in the book they invite us to follow Holzach on our own Manfred Bischoff journey.

The design of each individual book is of prime importance for Arnoldsche, and editor Rike Bartels and designer Gabi Veit show such a deep understanding of and sensitivity to how the work demands to be seen. The photos are contemplative windows into his opus, often framed by a vast amount of blank space, regularly shunned by so many publications as well as exhibition spaces because of costs, but here expertly curated into the page not simply as negative space but as a catalyst to look and think. The sheer quantity and depth of work makes this a truly slow book—every turn of a page challenging the reader’s imagination to (re)create the story behind each piece.

Both with their own deep personal connection to Bischoff, Bartels and Veit’s choice to match the cover piece, Afrodite unplugged, with the title of another, Ding Dong, is yet another testimony that with Bischoff nothing is ever quite what it appears to be. But Ding Dong represented so much more than a title, Bartels says: “the beauty of his script … the funniness of the title itself … the bells from the church … [its meaning of] ‘Voilà’, surprise … coming out of nothing.” Most of all, for Bartels it means that one day “somewhere from the horizon a tender voice says … ding … dong … it’s me … here. I am back!”[viii]

A universe is a home and a home is a universe, both so familiar and yet so complex. This book is a door to the home of Manfred Bischoff, a portal to his universe. We open it carefully, knocking to make sure we are not intruding, and once in we wait for the vortex that will suck us in. Such experiences are rare. When these books find us, they are ones we could never part with. These, too, are the rare books we elect as gifts for truly treasured friends hoping that they, too, can share in the journey.

[i] Pp. 13–15.

[ii] P. 45.

[iii] P. 71.

[iv] P. 127.

[v] P. 71.

[vi] Pp. 106–107.

[vii] P. 5.

[viii] Email exchange between the author and Rike Bartels, August 8–9, 2022.